Forced labor in Germany: Kaufering

c. August 1944 – March 1945

Jack Adler

Jack and Cemach stay in Auschwitz for only two weeks, at which point they are selected to go to a labor camp in Germany. However, as they are preparing for the transport, they must report to an SS officer and be registered by prisoner number. Upon arrival at Auschwitz, only those prisoners selected for forced labor are assigned a number, which is then tattooed onto their arm. Those selected for gassing or other assignments, such as medical experimentation, are not registered or tattooed. Jack has not been assigned a number and has no tattoo.

Transcript

Jack Adler: And we had to go through those selection processes again. Every day, they would select prisoners to be sent to various concentration camps. After two weeks in Auschwitz-Birkenau, my father and I were selected to be sent to Dachau, what turned out to be.

There was one problem. You see, those 50 boys, this was all in '44-- the Germans knew they were losing the war, so they tried to waste as little time as possible to complete their evil task. So the 50 boys weren't tattooed. I didn't have a number. I don't have a number.

And the process was when you were selected, the group that was selected to go to various concentration camps, you had to walk up to a table where an SS officer sat behind with a list, and you had to shout out the number you had tattooed. So my father told me when I come up to use the next consecutive-- [SOB] excuse me. [PAUSES FOR 3 SECONDS] To use the next consecutive number to his.

And his was 96037. So when I came up, they asked your number. I said, “96038.” And that's how I got out from Auschwitz-Birkenau.

"I didn't have a number. I don't have a number."

USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, Interview 18433

After another transport much like the one that brought them from Lodz to Auschwitz, Jack and Cemach arrive in Kaufering IV, a subcamp of Dachau. During the war years, Dachau becomes the center of an extensive network of subcamps developed to support the war economy with prison labor. At its greatest expansion in 1944-1945, the Dachau camp network encompasses more than 169 satellite camps with prisoners supplying slave labor to private and government industry, primarily in support of the war effort.

Map of the Dachau Camp System near Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Kaufering and the Dachau main camp are indicated.

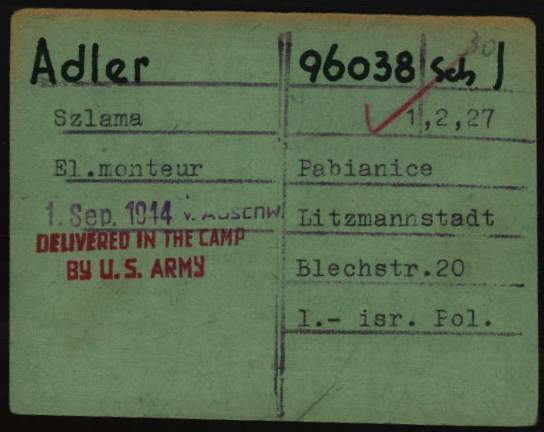

Prisoner card for Jack (Szlama) Adler from the Dachau prisoner office. The central administration for all camps in the Dachau system was at Dachau main camp. The card lists Jack’s prisoner number 96038, and indicates that he arrived from Auschwitz on September 1, 1944. The last line on the right side of the card “1. – isr. Pol.” identifies him as a Polish Jew. The prisoner card files were later used by the U.S. military to track individuals. At that time, the red stamp “Delivered in the camp by U.S. Army” was applied.

Arolsen Archives 10605904. [permission pending]

The first camp in the Kaufering subsystem is established in June 1944 to support the construction of underground facilities for the production of fighter planes. Allied bombings of German military and industrial targets have done substantial damage to the German aircraft industry, and fighter plane production is to be moved into subterranean bunkers to be constructed by prisoners.

Due to the general shortage of labor in 1944, for the first time since the Reich was declared “Judenrein” in 1942, some 30,000 European Jews are transported from concentration camps and ghettos in Eastern Europe to Kaufering. They are considered an expendable resource that will provide labor for the project; their sentence is death by work.

In order to disguise the camp from the air, the barracks at Kaufering are built partially underground and their low roofs are covered with grass. Inside these damp and cold shelters, prisoners sleep on bunks covered with straw. Together with the other prisoners, Jack and his father march one hour every morning and evening to and from an underground construction site, where they perform hard labor all day. They receive their daily ration of a slice of bread and a bowl of soup on site. Prisoners who are too weak to work are not fed.

Barracks at the Kaufering IV concentration camp. Hurlach, [Bavaria] Germany, April 29, 1945.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park [permission pending]

Transcript

Jack Adler: We-- we arrived in Dachau, in the city of Kaufering, Germany. Kaufering, which was under the jurisdiction of Dachau, the main camp, which was Dachau, which was only a few kilometers away, was erected, constructed specifically for the Jews from the ghetto. And they had 10 camps, 1 through 10. And my father and I were assigned to camp number four. And those barracks in-- in Birkenau, you had to walk down about three or four steps. The only thing you could see from the outside was a V-shaped roof, and grass grew on the roof.

And you-- and then as you marched down, there was a long hallway. There were shelves, like, on each side, where about 50 prisoners slept on each side, side by side. And at the end of the barracks, there was a window. [PAUSES FOR 3 SECONDS] And immediately, we were assigned to work at Kommando Mohl, M-O-H-L. They were constructing underground hangars for the German Air Force, so that they cannot be seen from the air. Because in 1944-- in 1945, the American and British air forces were bombing Germany around the clock. [PAUSES FOR 3 SECONDS]

And they should have only bombed Auschwitz and Dachau, but-- and they were aware of it, and they did not do anything about it. And that's another story. We know the names who were responsible by now for it, for this indecision.

So, my father and I were assigned to carry cement bags as they arrived by rail to the construction site, from the rail to the construction site. [PAUSES FOR 3 SECONDS]

"...my father and I were assigned to carry cement bags as they arrived by rail to the construction site..."

USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, Interview 18433

Conditions in the Kaufering camps are among the worst in the Dachau system. The primarily Jewish prisoners are expected to perform hard labor for up to fourteen hours per day with minimal sustenance. They are subjected to ongoing abuse by the guards. Nearly half of the prisoners in the eleven Kaufering camps will die due to malnutrition, disease, and mistreatment. Those incapable of work are deported and murdered.

Excerpt from Jack's memoir, Y? A Holocaust Narrative:

One day I was assigned to work with a group of men which happened to include my father. I was happy to see him, but I kept my emotions hidden and didn’t get overwhelmed with any sort of excitement. The soldiers that day told us we needed to move bags of cement from the rail to the construction site. This was among our most typical work. The bags were heavy and dusty and I choked all the while. Two of us carried one bag, but I was not paired with my father.

We weren’t allowed to slow down from the prescribed pace, if we did, one overzealous Nazi guard brandished a brutal weapon that was almost more sickening than the gun he held in his holster. A broomstick with a thick, long nail driven through it became his baton. When we dragged, he struck us on any exposed skin he could find and then he would laugh through crooked teeth as we bled.

I must have been too slow. I struggled with what number bag I’ll never remember. I felt something sting on the back of my neck before I realized what happened. The pain was fast and intense and I dropped to my knees in agony. I dropped the bag to my side and reached up for my neck. It was wet where I touched. The guard stood over me and threatened another blow in a language I was just beginning to understand without help.

Luckily, he growled some slur or another and continued down the line to find a new victim. My partner, a man I did not know, told me to get up and ignore the pain. As blood slid over my shoulder in a thin line, I got back to my feet, grabbing the bag of dry cement, and I continued to work. Some of the dust caked my wound and helped it to congeal. I was beyond tears that day. I would not cry in front of my father. I gritted my teeth and kept walking. For several hours more I carried the burden, the pain spreading down my spine like waves of liquid fire.

Later that night, when I finally returned to the barrack, I felt at the large, crusted scab on the back of my neck and fell asleep to images of the guard and his stick—laughing.

I still have a scar.

Jack Adler's Timeline

-

Jack Adler is born in Pabianice, Poland

Yakuv Szlama [or Szlomo] Adler (later: Jack Adler) is born to Cemach and Faiga Adler in Pabianice, a small city on the outskirts of Lodz in western Poland.

-

Europe's Jewish population is c. 9.5 million

This number represents 1.7% of the total population of Europe, and accounts for >60% of the world's Jewish population. Most Jews are in eastern Europe: Poland is home to 3.3 million Jews, some 2.5 million Jews live in the USSR, and around 756,000 Jews live in Romania. The Jewish population of the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia numbers c. 255,000. In central Europe, Germany is home to c. 523,000. Some 445,000 Jews live in Hungary, 357,000 in Czechoslovakia, and 191,000 in Austria. There are also large Jewish communities in Great Britain (300,000), France (250,000, and the Netherlands (156,000). Some 60,000 Jews live in Belgium. The Scandinavian countries are home to c. 16,000 Jews. In the South, the Jewish community in Greece numbers c. 73,000. Yugoslavian Jews number c. 68,000, Italy and Bulgaria each have communities of c. 48,000.

-

Dachau concentration camp established

Hitler's paramilitary SS (Schutzstaffel) establish the first concentration camp near Dachau for political opponents of the regime. Dachau remains in operation from 1933-1945. Over 200,000 people are imprisoned and estimated 41,500 are murdered during this period.

-

Polish Jews number c. 3.3 million

Jews have been living in Poland for 800 years. On the eve of World War II, Polish Jews constitute the largest Jewish community in Europe, accounting for 10% of the country's total population.

-

U.S.S.R. and Nazi Germany agree to non-aggression pact

Germany and the Soviet Union negotiate a non-aggression pact. This agreement, often called the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact after its chief negotiators, divides eastern Europe between the Nazi and Soviet powers and results in the partition of Poland.

-

Nazi Germany invades Poland, sparking World War II

Nazi forces invade and swiftly defeat Polish forces using the "Blitzkrieg"--a rapid and combined forces attack. Within days, Great Britain and France declare war on Germany, marking the beginning of World War II.

-

Nazi forces occupy Lodz and Pabianice, Poland

Invading German troops reach the city of Lodz and nearby Pabianice. They immediately introduce strict measures restricting the freedom of the Jewish population, in particular.

-

U.S.S.R. invades Poland

The Soviet military occupies eastern Poland, as secretly agreed with Germany in the non-aggression pact signed by the two countries on August 23, 1939 (Molotov-Ribbentrop pact).

-

Concentration of Polish Jews into ghettos ordered

Nazi officials order the concentration of Polish Jews in designated, often enclosed districts in major population centers in preparation for their deportation and murder. Ghettos are established throughout Nazi-occupied Poland.

-

Annexation of western Poland

Following the Nazi occupation of Poland, territories in the western part of Poland are annexed to Germany. Danzig-West Prussia and Warthegau are incorporated as new provinces of the Reich; the provinces of East Prussia and Silesia are expanded to incorporate newly gained Polish lands.

-

Generalgouvernement established in Nazi-occupied Poland

Nazis establish civilian administration over areas of Poland under German control that are not annexed to the Reich. The "Generalgouvernement" under the autocratic rule of Governor General Hans Frank encompasses four districts: Warsaw, Lublin, Krakow, and Radom.

-

Pabianice Ghetto established

Beginning in November 1939, Jews residing in wealthier areas of Pabianice are ordered to leave their homes, which are intended for Germans. In February 1940, the Jewish population is condensed into a designated area of the town. Jews are not permitted to leave the ghetto, the perimeter of which is indicated by signs.

-

Germanization of names in incorporated Poland

In areas of Poland under German administration, the names of Polish cities in the newly annexed territories are Germanized. Lodz is therefore also known as "Litzmannstadt."

-

Lodz ghetto established

Approximately 164,000 Jews are concentrated in a ghetto in the Polish industrial city of Lodz. They perform forced labor for the Nazi war effort, living under squalid conditions of severe overcrowding and insufficient sanitation, food and water.

-

Lodz ghetto sealed

The Lodz ghetto is sealed off from the rest of the city with barbed wire and fencing. Passage by Jews between ghetto and outside world is strictly controlled. Inside the ghetto, residents are forced to work in factories producing goods for the Nazi war effort. Many die of starvation and disease.

-

Jews deported from Lodz ghetto to Chelmno

Nazi forces and collaborators begin the deportation of Jews from the Lodz ghetto to the Chelmno killing center, where deportees are gassed in vans. Approximately 65,000 Jews are ultimately deported and murdered.

-

Wannsee Conference on the "Final Solution"

Leading Nazi officials convene at Wannsee to plan and implement the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question." At this meeting, operational preparations for the extermination of European Jewry are outlined.

-

Deadline for "Final Solution" in occupied Poland

Heinrich Himmler orders that by December 31, 1942 there should be no Jews remaining in the Generalgouvernement, calling for a "total purge" to secure the German Reich.

-

Nazi surrender at Stalingrad

After months of bitter fighting, the Soviet army is finally able to surround and trap German forces besieging the city. Of the nearly 250,000 troops that attacked the city in August 1942, some 90,000 surrender to the Soviets. The German defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad marks a turning point in the war; Soviet forces will now advance and push the Axis to retreat.

-

First prisoners arrive in Kaufering concentration camp

The first concentration camp at Kaufering is established with the arrival of 1,000 Jewish Hungarian men from Auschwitz. Kaufering will eventually become the largest subcamp complex in the Dachau system, with eleven camps located near Landsberg am Lech in Bavaria. It is also one of the most deadly Nazi labor camps: around half of the c. 30,000 prisoners sent to the Kaufering camps between June 1944 and April 1945 will die there. Prisoners in the Kaufering camps supply labor for the construction of underground aircraft production sites for the German airline industry, which has suffered heavy damage from Allied bombs.

-

Liberation of Majdanek

Advancing Soviet troops reach the Majdanek concentration and extermination camp. They find gas chambers and other evidence of genocide. Approximately 2,500 survivors provide details of the camp to their liberators, who document the horrors. Majdanek is the first concentration camp to be liberated by the Allies.

-

Liquidation of Lodz ghetto

Nazi forces liquidate the Lodz ghetto and deport between 60,000-75,000 Jews, as well as an unknown number of Roma, to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

-

American forces liberate Dachau

American troops reach Dachau and find approximately 32,000 inmates still alive, as well as 30 railroad cars with the corpses of prisoners who died in transport to the camp.

-

Unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany's High Command unconditionally surrenders on 7 May to the Allies and 9 May to the Soviets. May 8 is proclaimed "Victory in Europe Day."

-

US military opens hearings in Dachau trials

Between November 1945 and August 1948, the United States military holds hearings of camp guards, SS officials, and other personnel from the camps at Dachau, Flossenburg, Mauthausen, Nordhausen, Buchenwald, and Mühldorf. Of the 1,672 individuals tried before a military panel rather than a jury, some 1,400 are convicted. 297 are sentenced to death and nearly the same number to life imprisonment. Jack Adler provides testimony in advance of the trials.

-

Truman Directive prioritizes displaced persons for U.S. visas

President Harry S. Truman issues an executive order granting priority to displaced persons (DPs) for visas to enter the U.S. The order is expressly intended to help orphaned children. While it does not expand the restrictive U.S. immigration quotas, it enables some 41,000 DPs from Central and Eastern Europe – many of them Jewish – to enter the country between December 1945-July 1948.

-

Attacks on Jewish survivors in Poland

Attackers kill more than 40 Jewish survivors in Kielce, Poland. The attack spurs returning Jews to once again flee. Many find sanctuary in Allied displaced persons (DP) camps.

-

Jack Adler sails from Bremen to New York

Sailing on the S.S. Marine Marlin from northern Germany, Jack is one of 928 passengers on one of the first post-war transports of refugees from Europe to the United States. They arrive in New York harbor during the night of December 22 and disembark at Ellis Island the next day.

-

Jack Adler leaves New York for Chicago

After nearly a year and a half in New York, Jack learns that he has been placed with a foster family in Chicago and travels by train to meet them.

-

Korean War begins

After World War II, Korea is partitioned at the 38th parallel, creating a socialist state under Soviet influence in the North and a Western-style democracy in the South. In June 1950, North Korea invades South Korea, armed by the Soviet Union. Under the banner of fighting the spread of communism, the United States leads a UN coalition in the conflict against North Korea, which is backed by communist Russia and China. An armistice agreement in July 1953 puts an end to the military conflict, but the division of Korea persists until today.

-

U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America

When a request by the National Socialist Party of America (NSPA) to hold a White Power rally in the Chicago suburb of Skokie, IL, is denied at the insistence of the town’s large Jewish community, which includes many Holocaust survivors, the NSPA files a claim for infringement of their right to free speech under the 2nd Amendment. The NSPA is represented by lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union, who successfully argue in favor of the universality of free speech under the Constitution, maintaining that the government does not have the authority to selectively suppress voices, no matter how unpopular the opinion.