Life under Japanese occupation: Hongkew ghetto

Fred Marcus

While the United States battles Japan in the Pacific theater of the war, Fred and Semmy settle into their life in Shanghai. Although their circumstances are considerably more modest than they had been in Berlin, they are happy to be safe. They manage to stay afloat by selling some of the valuables they were able to bring with them, and Semmy pursues various business ventures to bring in income, including importing buttons from Japan.

Their situation changes after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The Japanese military launches an offensive on Shanghai and manages to gain control of the harbor and the International Settlement. Japan’s alliance with Axis powers Germany and Italy creates an uncertain situation for Jewish refugees in Shanghai.

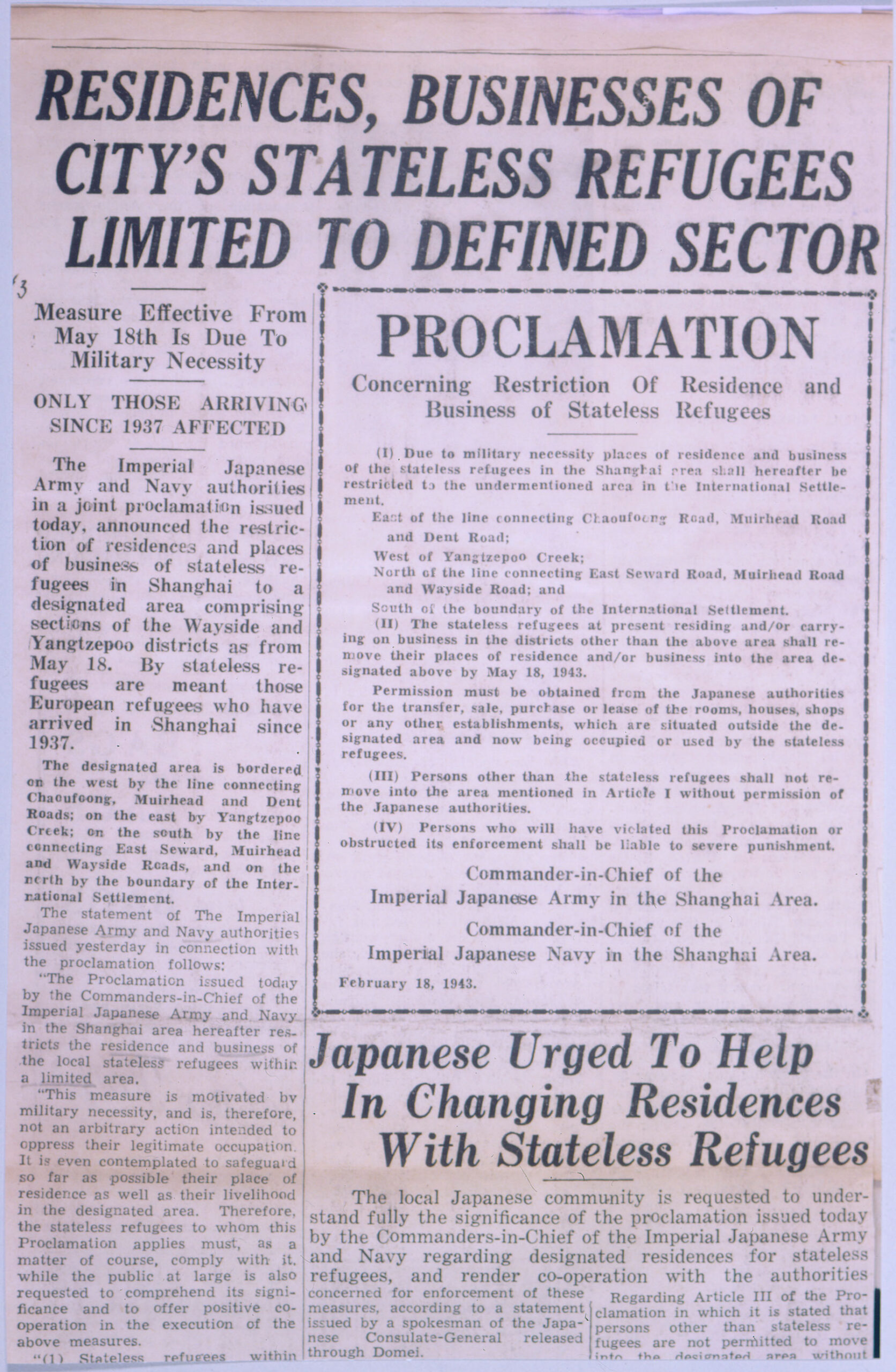

On February 18, 1943, at the urging of its Nazi allies and echoing the U.S. policy of internment of Japanese Americans, Japan issues the “Proclamation Concerning Restriction of Residence and Business of Stateless Refugees.” This orders all stateless refugees in Shanghai–most of whom are Jewish–to move to a designated area. Some 23,000 refugees move into an area officially known as the “Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees” that covers about one square mile in Hongkew, a neighborhood of Shanghai. They share this space with approximately 100,000 Chinese residents already living in that area.

While their Chinese neighbors may come and go freely, refugees’ movement in and out of Hongkew is restricted, cutting off their access to jobs and income. Living conditions for refugees in Hongkew are poor: makeshift housing is densely overcrowded with insufficient heating and sanitation; access to medical care is limited; and many refugees suffer from poor nutrition, all of which causes disease and hunger.

Soup kitchens operating with funding from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee continue to provide three daily meals to refugees until financial transfers to enemy countries are restricted under the Trading with the Enemy Act. These restrictions cut off this essential source of support to refugees in Japanese-occupied Shanghai. Thereafter, meal rations for refugees are cut down to only one meal per day.

An announcement printed in the North China Daily News proclaiming the establishment of a restricted zone in Shanghai for stateless refugees. February 18, 1943.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eric Goldstaub

Excerpt from Fred’s unpublished autobiography

They did not need to establish any fences or walls to keep us prisoners, because it was very simple to recognize that every Caucasian leaving the area was a refugee. (The Chinese in the area could come and go as they pleased.) All the Japanese had to do was to place signs at the intersections leading out of the Designated Area with the words: “Stateless Refugees Are Prohibited to Pass Here Without Permission.” It was a rather fiendish scheme on the part of the Japanese that they did not put us in a camp. They simply restricted our freedom, our liberty, and our mobility, without assuming responsibility for feeding or clothing us, or for providing us with medical care. We were on our own.

A sign from the Shanghai ghetto, which reads: "Stateless refugees are prohibited to pass here without permission." c. 1943

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Gary Matzdorff

Transcript

Fred Marcus: Let me just say that this was a strange ghetto, inasmuch as it had no walls or gates or barbed wire. In this totally Chinese neighborhood, all one needed to do--and what they did is--put up signs, "Stateless refugees not permitted beyond this point without special permission." And so you could see, if a Caucasian person went beyond, that was very easy to see. Not only that—the Japanese adopted the old Chinese [in Shanghainese], which every citizen serves for several hours a week as a police person. That's in Confucian times how Chinese society controlled itself without a professional police force.

And so we became [in Shanghainese] persons. We Jews had to control our fellow Jews not going beyond that certain point. And you've got a rope around your neck and the wooden batons. They give you a sort of a thing as an authority. And every week you had to put in two or three hours standing there, controlling your fellow Jews going in and out. So they didn't have any gates.

But the living conditions for many, not everybody, were abominable. Some people had built houses, bought houses, reconstituted houses. But others, great numbers lived in camps with still 30, 40 people in a room in double-decker bunks. And we lived sort of in a half situation, where we had a private room. As soon as my dad died, they put another man in with me, because I couldn't be just one person in a room--with very unsanitary conditions, but better than being in the camp.

So living conditions were abominable. Many people were unable to earn a living. And so the camps all had soup kitchens, and every Jewish inhabitant of Hongkew had the choice of getting a subsidy in cash—that means you took responsibility for buying your own food and cooking it—or to traipse once a day to the nearby camp with food stamps and get where much—how many stamps, you had so many scoops of whatever in huge cauldrons what, what was cooked for you. That's what I did then after my dad died.

"Let me just say that this was a strange ghetto, inasmuch as it had no walls or gates or barbed wire."

USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, Interview 9214

Fred Marcus' Timeline

-

Fred Marcus born in Berlin, Germany

His parents, Samuel and Gertrud Marcus, name their son Fritz Werner Marcus. He will later change his name to Fred Marcus.

-

Jewish population in Germany is c. 523,000

The c. 523,000 Jews living in Germany at the beginning of 1933 make up less-than 0.75% of the country's total population (67 million). Approximately 80% hold German citizenship; the next largest group are Polish citizens, many of whom are permanent residents of or were born in Germany. Some 70% of the Jewish population in Germany lives in urban areas; the largest community (c. 160,000 people) is in Berlin.

-

School quotas limit the number of Jewish students

Quotas allow only 1.5 percent of high school and university students to be Jewish. Jews will be totally barred from German schools by 1938, and Jewish schools will be ordered closed in 1941.

-

Law requires registration of Jewish-owned assets

Under the "Order for the Disclosure of Jewish Assets," Jews must register all property valued at over 5,000 Reichsmark. This law sets the stage for the expropriation of Jewish property and possessions.

-

Registration of Jewish-owned businesses

Businesses owned in whole or in part by those defined as Jews under the Nuremberg Race Laws must register, which allows for the further expropriation of Jewish property by the Nazis.

-

Restriction of Jews from professions

Nazi laws restrict Jews from employment in numerous professions, including: book-keeping, real estate, money-lending, and tour-guiding.

-

Kristallnacht Pogrom

Kristallnacht--the "Night of Broken Glass"--begins the night of 9 November and continues through the next day throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Nazi leadership plans and coordinates the pogrom, during which more than 1,400 synagogues are burned, Jewish-owned businesses destroyed, and about 30,000 Jews are arrested and deported to concentration camps. The Jewish community is later required to pay "restitution" for the damage caused to their own property. Nazis claim Kristallnacht was a "spontaneous" response to Grynszpan's assassination of vom Rath. In the United States, the Kristallnacht attacks were front-page news. Despite widespread condemnation of the Nazi persecution of Jews, the majority of Americans did not want to welcome Jewish refugees from Europe.

-

Exclusion of Jews from German economic life

The "Order for the Exclusion of Jews from German Economic Life" prohibits Jews from owning stores or engaging in any type of commerce with goods or services. Furthermore, Jews are prohibited from managing businesses of any kind and are forced to sell their businesses to Germans.

-

Jewish children banned from public schools

Jewish attendance at German schools has been subject to a restrictive quota since April 1933. Though most Jewish students had already left German public schools due to antisemitism, this law formally expells Jewish children from schools.

-

Fred and Semmy Marcus depart Berlin bound for Shanghai

With only a few personal belongings, some family heirlooms, and ten marks each in cash in their pockets, Fred and Semmy Marcus leave Berlin. They pass through Munich on their way to Genoa, where they board a ship bound for China on March 29.

-

Fred and Semmy Marcus arrive in Shanghai

After an exciting and comparatively luxurious 29-day passage, Fred and Semmy Marcus arrive at Shanghai pier and are transported to refugee housing.

-

US, Canada, and Cuba deny entrance of Jewish refugees on the St. Louis

The U.S., Canada, and Cuba deny entrance to over 900 refugees aboard the St. Louis, though they possess Cuban visas. The passengers--nearly all Jewish--are forced to return to Europe. Belgium, France, Great Britain, and Holland accept the refugees, though many are later deported and murdered when the Nazis occupy Belgium, France, and Holland.

-

Japan bombs Pearl Harbor

Nazi Axis power Japan bombs the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, killing 2,390 soldiers and civilians.

-

US enters World War II

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US declares war on Japan, as do Great Britain and the other Allied powers. The Japanese military attacks British forces in Shanghai harbor and gains control of the International Settlement in Shanghai, bringing the entire city under Japanese control.

-

President Roosevelt signs Executive Order for relocation of Japanese Americans

In reaction to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 mandates the internment of Japanese Americans with the stated purpose of preventing espionage. From 1942 to 1945, US government policy requires that people of Japanese descent in the US--including American citizens--are forcibly relocated to and held in isolated camps in the US interior.

-

Nazi surrender at Stalingrad

After months of bitter fighting, the Soviet army is finally able to surround and trap German forces besieging the city. Of the nearly 250,000 troops that attacked the city in August 1942, some 90,000 surrender to the Soviets. The German defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad marks a turning point in the war; Soviet forces will now advance and push the Axis to retreat.

-

Jewish refugees in Shanghai restricted to Hongkew ghetto

Japan issues the “Proclamation Concerning Restriction of Residence and Business of Stateless Refugees”, ordering the c. 23,000 stateless refugees in Shanghai—who are overwhelmingly Jewish—to move to a designated “Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees” in the neighborhood of Hongkew.

-

Samuel Marcus dies in Shanghai

Semmy's health has been poor since early April, and he is admitted to the hospital on April 20th. Fred is himself struggling with pneumonia and his infection keeps him from visiting his father as he fights a severe fever for 8-10 days. When Fred’s fever subsides, he learns that his father passed away on May 1.

-

D-Day: Allied invasion of France

The long awaited invasion of Nazi-occupied France by Allied forces begins with the landing of some 175,000 US, British and Canadian troops on the beaches of Normandy.

-

Death of US president Franklin Roosevelt

Following a stroke, President Franklin Roosevelt dies. Vice President Harry Truman becomes President.

-

Unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany's High Command unconditionally surrenders on 7 May to the Allies and 9 May to the Soviets. May 8 is proclaimed "Victory in Europe Day."

-

US atomic bombs destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The US drops an atomic bomb on Japan's manufacturing and port city Hiroshima on 6 August. The bomb obliterates the city, killing nearly 80,000 people, mostly civilians. On 9 August, the US drops another atomic bomb on Nagasaki, killing at least 40,000 people.

-

V-J (Victory over Japan) Day: Imperial Japan surrenders

Imperial Japan announces surrender to the Allies, ending World War II. Formal surrender ceremonies follow on 2 September.

-

Emigration crisis for displaced persons (DPs) in Europe

Two years after the end of the war, there are still some 1 million people in displaced persons (DP) camps in Europe. Approximately 250,000 are Jews awaiting further immigration, many of whom wish to emigrate to Palestine. For many DPs, repatriation to their pre-war homes is unthinkable, but many countries--including the U.S.--still impose restrictive immigration policies.

-

Exodus sails for Mandate Palestine

The ship Exodus embarks from France carrying approximately 4,500 Jewish refugees bound for British Mandate Palestine. British forces prevent the ship from docking and return it to France, where refugees remain on board for over a month. British administrators enforce a strict quota on Jewish immigration at the demands of Arab leaders in Mandate Palestine.

-

US Congress passes Displaced Persons Act

At the urging of US President Truman, Congress passes the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 allowing for the entry of 100,000 DPs from Europe per year, greatly expanding the previously enforced national origin quotas. The Displaced Persons Act is amended in 1950. In total, 400,000 DPs immigrated to the US between 1948-1952, including an estimated 80,000 Jews.

-

Fred Marcus departs Shanghai bound for San Francisco

Nearly ten years after his arrival in April 1939, Fred Marcus boards the S.S. Joplin Victory in Shanghai Harbor, headed for San Francisco and a new life.

-

Communist forces led by Mao Zedong reach Shanghai

Rural China has been in the midst of a civil war between the Chinese nationalist Kuomintang led by Chiang Kai Shek and the Communist opposition led by Mao Zedong since the end of Japanese occupation in 1945. As Communist forces under Mao Zedong reach Shanghai, a Communist takeover in China is all but certain.

-

The Jewish population of Europe is an estimated 3.5 million

In 1933, Europe was home to an estimated 9.5 million Jews. By 1945, two out of every three have been killed. Before the war, Poland had the largest Jewish population in Europe, numbering some three million. An estimated 350,000 Polish Jews survived the war, and by 1950, only 45,000 remain in Poland. The lives lost in the Holocaust account for most of these demographic changes. For most survivors, a return to their pre-war lives is unthinkable, and they seek to start a new life abroad.